I co-authored this article with Andrew Bowman, a research fellow with the University of Manchester’s Centre for Research on Socio-cultural Change (CRESC) and Financial Times blogger, originally published in Red Pepper in August 2012.

While the eurozone teeters on the brink, construction work is underway in Frankfurt’s financial district on new headquarters for the European Central Bank (ECB). Due for completion in 2014, the 185 metre tall, futuristically designed skyscraper will have double the office space of the ECB’s current residence, the Eurotower. It embodies the expectations for the future of the single currency from the one institution that has no future without it.

As the drama of the financial crisis has unfolded over the past five years, press coverage and political debate has tended to focus predominantly on the actions of national political leaders. At many points, however, the back-stage central bank officials have been the most influential actors.

Nowhere is this truer than with the ECB. With EU decision-making processes incapable of reconciling national and pan-European interests, and in the absence of a fiscal policy for the eurozone, the ECB has filled the gap.

Prime ministers struggling to control their countries’ borrowing costs, banks struggling to remain liquid during the prolonged credit crunch, and that most elusive of entities, ‘the markets’ seeking a ‘return to confidence’, have all turned to the ECB. Along with the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England, it has acted as a life support system for the west’s bloated financial sector.

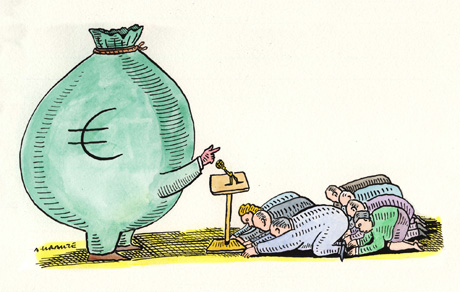

Central banks are the most politically powerful yet under-examined institutions in contemporary capitalism. This is because central banks are not expected to be powerful in the political sense. Modern central banking is premised upon the assumption that central banks are politically neutral technocrats, that their activities are primarily limited to controlling price inflation via simple mechanisms, and that as such they can operate independent of formal political controls.

The crisis has seen this script torn up, as central banks, the ECB in particular, have stepped out of their agreed roles to fulfil various controversial functions: a provider of indefinite, no-strings-attached welfare for the banking system, the key arbitrator in disputes over the sustainability of sovereign debt with the power to topple governments, and, in the case of the ECB, the most forthright proponent of fiscal austerity and further undemocratic European integration. It’s time we took a closer look.

History

Since the first central banks were established in the 17th century, they have always had a fraught relationship with politics. Their duties, methods and independence have all been periodically renegotiated: from an original role helping the state raise war funds, to an independent ‘bank for the banks’ during the pre-1914 gold standard, to a servant of state growth and employment policies post‑war. The stagflation crisis of the 1970s and the political triumph of neoliberalism brought a narrower ‘monetarist’ focus, targeting inflation through control of the money supply and later short term interest rates.

Formal independence from the corrupting influences of democratic politics – blamed for the central banks’ inability to control 1970s inflation – became the ideal. The historical role as a guardian of financial stability became a lesser priority because risk-spreading financial innovation and advances in the ‘science’ of monetary policy were assumed to have made financial crises less likely.

The ECB bears these influences, but is best understood as the progeny of the German Bundesbank. Monetary stability is a sensitive topic in German history. Hyperinflation paved the way for the far right in the 1930s, and Hitler’s initial economic successes involved forcing the Reichsbank to fund re-armament. Post-war, the Reichsbank was abolished, most of Germany’s gigantic debt was written off in the Marshall Plan, and the independent Bundesbank was established to ensure there would be no repeat.

Staunchly anti-inflation and viewing expansionist fiscal policies as dangerous, the Bundesbank was integral to the German ‘Ordoliberalism’. It claimed responsibility for the wirtschaftswunder of post-war Germany, frustrated successive German chancellors, and turned the Deutschmark into Europe’s ‘hard currency’. Monetary policy across the continent followed the Bundesbank’s lead in constant cycles of currency adjustment.

The euro is usually portrayed either as a naive idealist or nefarious quasi-imperialist political project. However, it was also born out of unromantic monetary policy aims: to end exchange rate instability and currency speculation, to give Germany a weaker currency to boost its exports, to free France from subordinate status to the Bundesbank, and to reduce obstacles to investment.

Leaving the Deutschmark was not easy for Germany. As Helmut Kohl is reported to have said to Mittterand while discussing the single currency: ‘The D-Mark is our flag. It is the fundament of our post war reconstruction. It is the essential part of our national pride; we don’t have much else.’

To placate concerns, the ECB was located in Frankfurt, with a similar governing structure and remit to the Bundesbank, including a primary objective of price stability. The single currency would not work, it was suggested, should monetary policy be subject to bartering between different national governments. Therefore, while monetary operations would be implemented by national central banks (NCBs), the ECB would make decisions independently of government via a combination of a six-person executive board and representatives of the eurozone NCBs. Its decision‑making meetings would be secret. Constitutionally, it was made illegal for the ECB to take instructions from EC institutions or national governments, or to finance member states’ spending by directly purchasing their bonds. In the absence of a counterbalancing fiscal authority, this placed the ECB among the world’s most powerful and unaccountable central banks.

Managing the crisis: enforcers of austerity

The euro initially posed none of the problems that detractors had foretold. The eurozone shared in the so-called ‘great moderation’ of the 2000s: steady growth, low inflation, low interest rates and light-touch financial regulation. The credibility of central bankers climbed and, like the Fed and Bank of England, the ECB became a cheerleader for financial services.

Boom-time ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet assured doubters that integration would flatten out eurozone economic imbalances: capital would automatically move to wherever it could be most efficiently used, without any politically controversial fiscal redistribution. The higher growth rates of Ireland, Greece, Spain et al during the early 2000s appeared to confirm it. Major investment banks thrived, taking capital from north European nations running budget surpluses – particularly Germany – and investing it into credit bubbles in the eurozone periphery. Alongside the bubbles, widening differences in balance of payments, wages and inflation were largely ignored.

The pre-crisis hubris of central bankers rested on confidence in the predictive capacity of monetary economics, which – as with economics in general – had become more esoteric and algebraically complex. This ‘scientisation’ also bolstered claims of political neutrality. Post-crisis, the facade crumbled.

The ECB responded to the credit crunch in 2007 with bank liquidity provision that carried on over the following years. Unlike the Bank of England and the Fed, it did not engage in mass purchases of government bonds – quantitative easing (QE) – because of its mandate to not finance governments, the rationale being that it dis-incentivises budgetary prudence. The ECB followed Angela Merkel in denouncing ‘Anglo-Saxon’ QE as an inflationary risk.

The eurozone debt crisis starting in Greece from May 2010 forced a reversal. The ECB had either to wade into the bond market and monetise peripheral government debt to lower borrowing costs and reduce the default risks to banks holding the debt (anathema to Bundesbank principles) or potentially see the currency union disintegrate.

It waded in, buying up €74 billion of Greek, Portuguese and Irish government debt via the securities market programme (SMP) in the secondary bond market (buying bonds from existing bondholders rather than directly from the governments). With plummeting demand brought on by the disastrous austerity programmes, the calls for action on the part of the ECB have been unrelenting. When the SMP stopped in March 2011, bond yields began rising again. With Spain and Italy sucked into the crisis, and the European financial stability facility (the EU’s temporary bailout fund) proving inadequate, the ECB stepped in again, buying €210 billion of distressed sovereign debt in 2011, at a rate of around €14 billion per week that summer.

The ECB has used its power selectively, though, while being attacked by Merkel for being too indulgent, and by Sarkozy and Cameron (who implored it to wield ‘the big bazooka’) for the opposite. Tussles over the size of the SMP created dissension within the ECB, with both Jürgen Stark, the German ECB chief economist, and Axel Weber of the Bundesbank quitting the organisation in protest.

For the people of the eurozone periphery, ECB action has come at a price: austerity. The ECB is famously allergic to any hint of political interference in its affairs. But Frankfurt has no inhibitions about the reverse, intervening regularly in the affairs of democratically elected governments. Current ECB president Mario Draghi follows his predecessor in reiterating the fallacy that irresponsible government spending has caused the crisis – an analysis which conveniently exonerates them of their own shortcomings – and presses home the message in dealings with bailout recipients.

Most citizens in ‘programme countries’, a euphemism for their diminished-sovereignty status in return for bailouts, will be familiar by now with the dreaded quarterly arrival of inspectors from the troika – austerity and structural adjustment monitors from the EC, IMF and ECB. After seeing this humiliating and almost total surrender of fiscal sovereignty, Portuguese PM Jose Socrates and more recently his Spanish counterpart Mariano Rajoy baulked at suffering a similar indignity. It took a financial coup d’etat by the ECB to bring Socrates to heel.

‘I have seen what happened to Greece and Ireland and do not want the same happening to my country. Portugal will manage on its own, it will not require a bailout,’ he declared. A few days after he finally succumbed in April last year, it emerged that the ECB chief had forced his hand by pulling the plug on the state. When Portuguese banks announced they would no longer purchase bonds if Lisbon did not seek a bailout, Socrates had no choice but to request an external lifeline. Later in the week, the head of the country’s banking association, Antonio de Sousa, said that he had had ‘clear instructions’ from the ECB and the Bank of Portugal to turn off the tap. Even hardened cynics in Lisbon and Brussels were staggered, privately saying the ECB had crossed a line.

In August last year, the ECB swooped in to rescue Italy and Spain in a massive bond-buying programme after yields reached levels approaching those faced by Greece and Ireland when they applied for aid from international lenders. A secret letter made public by Italian daily Corriere della sera from then ECB chief Jean-Claude Trichet and his successor Mario Draghi delineated the quid pro quo for this assistance: still further austerity and labour market deregulation. The letter told the Italian government exactly what measures had to be instituted, on what schedule and using which legislative mechanisms. The ECB, unelected and unaccountable, was now directing Italian fiscal and labour policy. In secret. Even Silvio Berlusconi said at the time: ‘They made us look like an occupied government.’

When Greek PM George Papandreou announced last October he would hold a referendum before his government could agree to a second bailout and still deeper austerity, markets threw conniptions. On 2 November, the ‘Frankfurt Group’ (GdF for short, as per the letters on their lapel badges identifying them to security) – an unelected, self-selected octet established last October, reportedly in the backroom of the old Frankfurt opera house during the leaving do for Jean‑Claude Trichet – called him in for a dressing down.

The GdF at the time comprised IMF chief Christine Lagarde; German chancellor Angela Merkel; French president Nicolas Sarkozy; newly installed ECB chief Mario Draghi; EC president José Manuel Barroso; Jean‑Claude Juncker, chairman of the Eurogroup (the group of states that use the euro); Herman van Rompuy, the president of the European Council; and Olli Rehn, EU commissioner for economic and monetary affairs. They had decided that they had had enough of this man who was incapable of forcing through the level of cuts and deregulation they demanded.

Days later, Papandreou pulled his referendum and resigned to be replaced by unelected technocrat Lucas Papademous, former ECB vice president and negotiator when Greece applied for its first bailout. The troika had gone one step further than the manoeuvre that forced the Portuguese leader to sign up to a bailout against his will: they had for the first time toppled a government and suspended Greek democracy, installing one of their own. Days later, they would do the same in Italy.

If the toppling of Greece’s prime minister was more of a European-politburo group effort, albeit with the ECB at its heart, most analysts are clear that the overthrow of Berlusconi, untouchable even after 18 years of court cases, bunga-bunga sex parties and corruption scandals, was effected directly by the ECB. As Italian bond yields soared to 6.5 per cent, near the danger zone at which Athens, Dublin and Lisbon signed up to bailouts, it was widely reported that ECB chief Draghi was pressuring Berlusconi to step down. This was signalled by very limited Italian bond-buying by the ECB on the Monday before he resigned to be replaced with ex-EU commissioner Mario Monti. This bond-market weapon at Frankfurt’s disposal was of an order of magnitude greater than any domestic pressure from within Berlusconi’s own party or the opposition.

Toppling two prime ministers in a week served as a muscular, unambiguous warning to other governments that the ECB giveth and the ECB taketh away. When Spanish PM Mariano Rajoy was dragging his feet in requesting a bailout, aware that he would be surrendering his country’s sovereignty, pressure was mounted on Madrid to capitulate. In perhaps a polite reminder to Rajoy of their role in Berlusconi’s ousting, ECB governing council members publicly encouraged him to avoid delay.

Proposals for moves towards an EU ‘political union’ unveiled on 25 June by the self-selected quartet of the presidents of the European Council, European Commission, Eurogroup and ECB go well beyond the centralised EU review of national budgets and fines approved last year, and towards a pooling of sovereignty without democratic oversight. Brussels would be given the power to rewrite national budgets, and if a country needs to increase its borrowing, it would have to get permission from other eurozone governments. This is in line with the vision of political union ex-ECB chief Jean‑Claude Trichet outlined last June when still in office – of a centralised veto over national budgets jointly wielded by the commission and council ‘in liaison with’ the ECB, with overspending governments ‘taken into receivership’.

The ECB vision, expressed on a number of public occasions by Trichet and subsequently his successor, was described by the former as a ‘quantum leap’. It involves two aspects: a radical liberalising programme of labour market deregulation, pensions restructuring and wage deflation on the one hand; and on the other for fiscal policy to be taken out of the hands of parliaments and placed in the hands of ‘experts’ – in the long-term an EU finance ministry – in the same way that monetary policy has been removed from democratic chambers and placed in the hands of Frankfurt.

Orthodox analysts are quite sympathetic to the goals of the central bank. As Jacob Funk Kirkegaard of the Petersen Institute, the Washington economic think‑tank, has written, ‘The ECB is in a strategic game with Europe’s democratic governments,’ an overtly political strategy that is ‘aimed at getting recalcitrant eurozone policymakers to do things they otherwise would not do.’ The bank ‘is thinking about the design of the political institutions that will govern the eurozone for decades.’ For Kirkegaard and a number of other long-time ECB watchers, the main target is ultimately not Spain or Italy, but France, historically resistant to more binding eurozone fiscal rules viewed as a radical infringement of its sovereignty. By doing little in the face of market attacks on Spain and Italy, Frankfurt is warning Paris and its new president that it has no choice but to accede to its vision of technocratic fiscal governance.

Bank welfarism

The ECB’s ruthless approach to indebted sovereign states contrasts sharply with its approach to the banks. Dwarfing its support for sovereign debt is the vast quantity of easy liquidity extended to the banks since the start of the crisis.

The sovereign debt crisis has in reality always been a continuation of the banking crisis of 2008. In the absence of serious reforms, banks have remained fragile, over‑leveraged and highly interconnected across borders. Sovereign defaults would spell disaster for many major banks in core eurozone economies – not to mention the UK – which, running short of safe AAA investment opportunities and armed with new liquidity from their central banks’ support programmes, looked south in 2008/09 to invest in peripheral sovereign debt. Bailouts of these states were bailouts for banks too.

Besides default risk, the sovereign debt crisis poses additional problems for the banks. Most depend heavily upon short-term borrowing in inter-bank money markets, in which they have to pledge assets as collateral for receiving a loan. Once a lender has received this collateral from a borrower, they can also use it as collateral for their own borrowing, building up a chain of debt in a process known as ‘rehypothecation’.

Pre-crisis, the now-infamous AAA asset-backed securities were important for their use in collateralised lending. But once their value got questioned and their rating dropped, they were no longer eligible – a major factor in causing the credit crunch. Government bonds are generally accepted as safe collateral to be used in lending, but the debt crisis and downgrades of peripheral debt by the rating agencies has made many of them ineligible, compounding the liquidity problems.

The ECB has stepped into the breach to support the banking sector, providing continuous rafts of cheap loans to effectively keep zombie banks on life support. Since 2007, ECB lending to eurozone credit institutions has more than tripled from around €400 billion to more than €1,200 billion. The ECB balance sheet has expanded from around 15 to more than 30 per cent of eurozone GDP.

By continuing to accept the ‘non-marketable’ collateral, the ECB allows banks to exchange their bad investments made in the boom years for the highest quality form of money: central bank reserve money.

These actions began with the onset of the credit crunch in August 2007, when the ECB took swift action to inject €95 billion of overnight liquidity into distressed eurozone banks. This continued over the coming years, but the most dramatic intervention took place in December 2011, with the long term refinancing operation (LTRO), a dry sounding name for an unprecedented action.

With the eurozone banking system feared to be on the verge of a Lehman’s-style collapse, the ECB provided an unlimited supply of 1 per cent interest, three-year collateralised loans to the banking system, once on 21 December 2011, and again on 28 February 2012. The total amounted to around €1 trillion, with takers including nearly all of the eurozone’s major banks, and many from the UK as well. Given that banks used their bad assets as collateral this amounted almost to free money.

The stated aim of the LTRO was to get banks lending again to the ‘real economy’. However, there is little evidence to suggest this happened. Analysts at ING bank estimated that of the €489 billion lent in the December 2011 LTRO, for example, a mere €50 billion found its way back into the economy.

One of the outcomes of all this assistance has been the banks using the ECB’s easily accessible loans to undertake a ‘carry-trade’ – borrowing money at low interest rates and lending at higher ones – with eurozone governments. Forbidden from lending directly to governments, the ECB lends cheaply to banks, which in turn lend to governments and receive much higher interest rates in return. Spanish banks, for example, have reportedly bought €83 billion of Spanish government bonds since December. This is more than just an easy money spinner: it binds together more tightly the relationship between commercial banks and the state, meaning that each cannot survive without the other.

As a result of this support to the banks the ECB now holds a large portfolio containing hundreds of billions of euros worth of dodgy bank assets. This goes well beyond acting as a ‘lender of last resort’ to the banking system – a traditional expectation of central banks – and represents a mass transfer of risk from private to public spheres. The value of these assets, many of them tied to over-inflated property markets, remains deeply uncertain.

The outcome for central banks is unclear. Some economists argue that they cannot go insolvent since they can print money; others fear this would create a loss of confidence in the currency and that an expensive (and politically explosive) recapitalisation of the ECB by eurozone governments would be required.

Central banks’ financial sector support operations have been widely portrayed as technical measures to keep the credit system moving. But their sheer size raises a political question: why should a public institution keep a banking industry so large, so fragile and with such a dubious social contribution running in its present form?

A growing body of opinion suggests that the banking system is simply too large and too complex, and that the only reasonable solution is to shrink and simplify it – to return banking to a utility function. But these more radical reforms are being kept off the table by the central banks’ financial-sector welfare regime, which effectively preserves the system in its present form.

And just like the worst stereotype of welfare dependency dreamt up by the right-wing press, the recipients of the bank welfare regime – as their handling of the Libor scandal shows – exhibit a lack of concern for the common good and an unwillingness to change their ways. In comparison to the punishing austerity exacted on the eurozone periphery, or the public sector restructuring in the UK, banking reforms have been featherweight.

What of the future of central banks? Both the Bank of England and, it now seems likely, the ECB are to be handed additional responsibilities in bank regulation. If the pattern continues, it is one of governments moving ever greater responsibility for economic decision‑making beyond the sphere of democratic control. An intriguing issue raised by the central banks taking the bad assets of the commercial banks onto their balance sheet is whether they may eventually come to be responsible for writing them down, using their unlimited money-creating capacity to act as an agent of debt cancellation. In the face of the likely financial turbulence and economic changes ahead, central bank independence looks untenable.

This independence was premised upon three things: technical competency, political neutrality and a strict limitation of activities. In the case of the ECB and the other major central banks all three conditions have been trampled over. In the UK, as evidence of collusion in corrupt Libor manipulation between the Bank of England and the major commercial banks comes to the surface, it’s a good time to put democratisation of the banks back onto the agenda.

This article is developed from an ongoing ‘Central bank-led capitalism?’ research project at the University of Manchester’s Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change. Free working papers analysing the crisis are available at www.cresc.ac.uk